For two decades, the words “cinematic” and “blockbuster” have been, for most game directors, synonymous. During this window, which stretches back to the original God of War and Halo, we’ve enjoyed (or, for others, endured) big-budget video game creators aspiring to emulate their blockbuster film counterparts.

If — somehow — you’ve never seen the films of Steven Spielberg or Michael Mann, you’ve nonetheless experienced them via contact highs from Uncharted, Grand Theft Auto, and practically every other Big Game released this millennium.

But Indika, a game that sounds like a weed strain and plays like being stoned and scrolling through the Criterion Channel, has me hopeful that we’re approaching, with narrative video games, a turning point for what it means for a game to be “cinematic.”

What fuels that hope is Indika’s creative similarities to a micro-budget indie horror film from the ’90s.

The Blair Witch effect

Is it possible for one game to change the look of an entire medium? And why would it be Indika, a game most readers haven’t played, or even heard of?

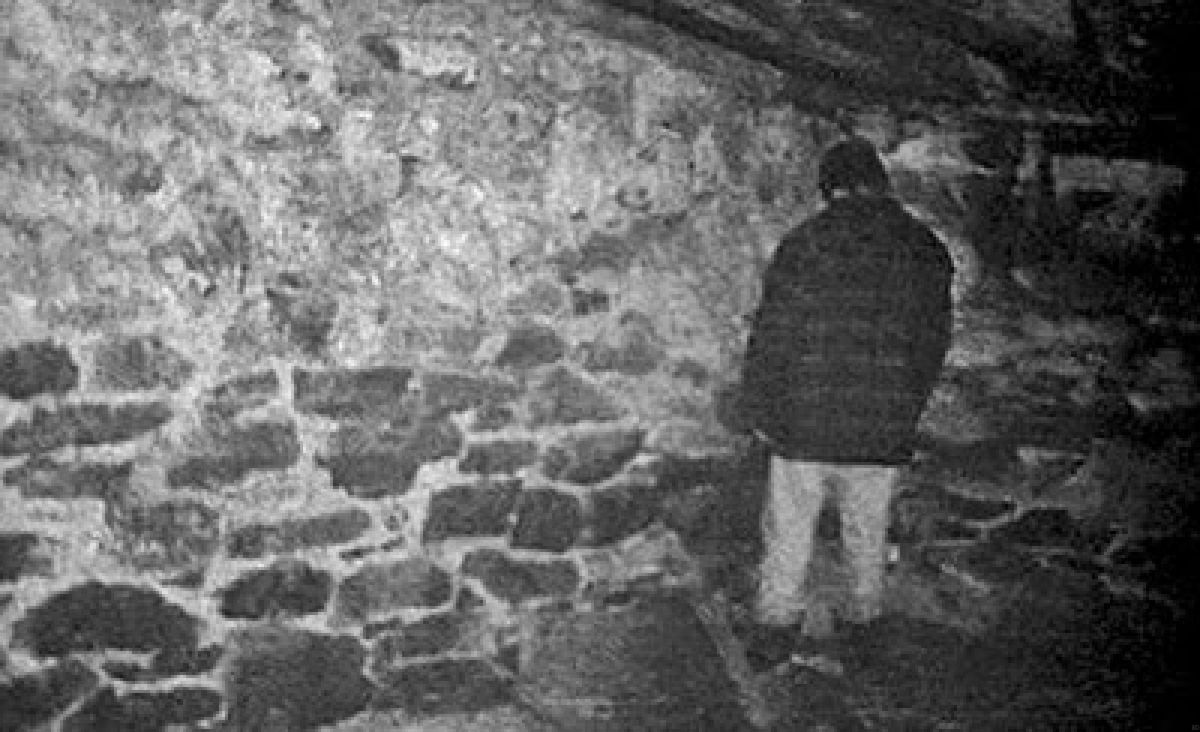

25 years ago, The Blair Witch Project inspired countless parodies with a single shot. You know the one. You can see it in the trailer, the poster, or at the top of this story. The lead actress-slash-camera operator holds a cheap camcorder inches from her face. Tears well in her eyes, and a flashlight casts hard shadows across her dry skin.

She’s terrified. She’s a mess. She’s barely in focus or even in frame.

At that time, few commercial directors would film a shot so crudely, nor would a celebrity offer the audience such an intimate look inside their nostrils. Filmgoers expected movies to conform to a certain look, sound, and feel. But The Blair Witch Project didn’t resemble anything in theaters; it looked like a cheap documentary you’d find on the local PBS station. It looked real.

With that emphasis on “realism” above all else, the amateur camerawork accomplished its goal — scare the shit out of people — better than any expensive shot on an industry-grade camera could.

The filmmakers had taken the empathic visual language of the documentary form and weaponized it. Look again at the shot. You don’t see an actress staring into the camcorder; you see a person. And so, as happens when you look someone in the eyes, a connection forms. This person, you think, could be you. Alone. In the woods. Something unknown stalking through the branches.

The camerawork of The Blair Witch Project wasn’t cinematic, not in the classical sense. But in time, what audiences expected film and TV to look like would change to meet that image. Do we have the sprawling found-footage horror genre without it? Or the mega-popular docu-sitcoms like The Office and Modern Family?

The creators of The Blair Witch Project, because of their limitations (no money! No sets! No actors!) looked for inspiration where others didn’t have to, and wouldn’t choose to. The film’s success then gave future creators big and small permission to follow its lead, forever changing what a Hollywood movie could look and feel like.

Indika and the film school games

Indika, the fantastic new adventure game from Odd Meter, tells the story of a young nun who loses her grip on reality in an alternate-history version of 19th-century Russia. Tortured by a voice in her head that may or may not be a demon, Indika partners with a sickly man who may or may not be divinely chosen by God. Together, they embark on a perilous road trip through beautiful forests, abandoned towns, and literalizations of biblical allegory.

Indika is the latest — and one of the most impressive — examples of a sea change in the look and feel of cinematic games.

You don’t have to play Indika to see what I mean (though, hey, you really should). In the announcement trailer, the game’s creators borrow liberally from filmmakers rarely associated with games. These directors, who can’t afford the spectacle and scale of big-budget filmmaking, rely on more audacious (and affordable) craft to distinguish their work.

“We tried to use a standard limited set of [virtual camera] lenses to depict the limitations of inexpensive auteur cinema,” Indika game director Dmitry Svetlow told Polygon over email. He cited Poor Things director Yorgos Lanthimos, Russian filmmaker and slow cinema pioneer Andrei Tarkovsky, and former Monty Python member and infamous weirdo auteur Terry Gilliam as inspiration.

In Indika, the stark exterior landscapes and cold architecture resemble the striking but antiseptic sets of Lanthimos. In the game’s nunnery, a SnorriCam shot — in which the camera is strapped onto the actor and aimed at their face — recalls Blair Witch, of course, but also the works of ’90s music video director turned ’00s filmmaker Spike Jonze and Robert Webb’s comedy sketch series Sir Digby Chicken Caesar.

Where Blair Witch borrowed the documentary aesthetic to force audiences to straighten their backs and pay attention, Svetlow and company are reaching into the toolbox of low-budget filmmaking to do something similar with games.

Or, to put it crassly, Indika doesn’t just look like art films but feels like them. The story opens with the player inhabiting the habit of the titular young nun and fetching a pail of water from a well, then doing it again. And again. And again and again. Her steps up and down a grimy, snow-crunched slope in the abbey echo Tarkosvky’s long shots (like this one of a man carrying a candle for seven minutes) that were intentionally tedious, forcing us to feel time passing not just in a movie or a game, but in our life as we experience them.

To make the game more cinematic, Svetlow wrote the team needed a “greater focus on dramaturgy, on the quality and depth of characters, as well as the necessary level of presentation of events.”

In Indika, you don’t save the world or nail sick headshots. You accumulate poorly hidden collectibles and earn points, though they’re worth nothing and, by the standards of other games, a waste of time — something the game’s loading screens emphasize any chance they get. (“Don’t waste time collecting points, they are pointless.”) Sometimes Indika comes across a bench, and if you direct her to sit down on it, the game hands over the “film editing” to the player, allowing them to swap between different camera angles, some of which Indika doesn’t even appear in.

You could move on, directing Indika to stand back up and continue about her business. Or you could let the camera rest, your mind wandering as your eyes lock onto a field of mud and snow. In a medium full of realistic 3D worlds rife with kinetic empowerment, Indika encourages you to indulge in a moment of peace and ceding of control.

Change happens slowly and then all at once

Can we be certain games like Indika will influence their big-budget peers? They already have.

Here’s just one example: In 2009, Naughty Dog released Uncharted 2, a game rife with some of the most iconic blockbuster moments in the history of video games. Its opening, in which the hero climbs up a train that dangles off a cliff, may have inspired the latest Mission: Impossible, which ends with Tom Cruise doing something very, very similar.

But tucked into Uncharted 2 is a sequence meant to contrast with these sorts of set-pieces. Around the midpoint, Nathan Drake hikes through a Tibetan village. He doesn’t climb any deadly cliffs. Nothing blows up. Nobody gets shot. This was, in its time, unusual — a moment in which the player could exist in a beautiful 3D environment without being required to destroy the village or its population.

The Tibetan village sequence (and I swear this was acknowledged publicly, though now I struggle to find any quote) was cribbed from 2008’s The Graveyard, a short art game from the now-defunct micro studio Tale of Tales. In the game, an elderly woman walks the path of a graveyard, sits on a bench, reflects, and then returns from where she came. To younger readers, this will sound tedious. But to game critics at the time, this scene dropped into our minds like a new drug — a total shock to the system.

With The Graveyard and Uncharted 2 and many other (mostly indie) games of that time period, the video game industry witnessed a surge in what would be dubbed “walking simulators,” a somewhat derisive term for a powerful idea: You make a beautiful, rich virtual space, then afford your players some time to exist within them.

If The Graveyard could reshape the assumptions of cinematic video games, then why shouldn’t Indika help to bring the style of low-budget and arthouse filmmaking to Indika’s many peers?

That’s the magic of this moment in video games: Indika isn’t alone in its ambitions to challenge our assumptions of what makes a game cinematic. Indie developers have been steadily pushing against the confines of what games look and feel like for over a decade. To the Moon. El Paso, Elsewhere. Disco Elysium. I could double my word count with nothing more than titles.

But what’s different now, and what Indika reflects, is the independent games scene accelerating up an exponential hockey stick of creative output.

Much like The Blair Witch Project (and countless other indie films since its release) was made possible by the first boom of consumer-level cameras and filmmaking tools, Indika and its ilk reflect a new era of game production where a small team — thanks to cost-effective and ultra-powerful dev tools — can take a risk on a personal project. In fact, with modern game engines, indie game developers can accomplish visual feats indie filmmakers could only imagine.

“We recreated a non-existent fairy-tale world; to do this for cinema would have cost an order of magnitude more,” Svetlow told Polygon.

Since I finished Indika, I’ve played three more oddly “cinematic” games — Arctic Eggs, 1000xResist, and Crow Country — and it feels like every week another new game appears, its creators taking a bat to the expectations of what a game should look and feel like. Now and then the bat is bound to connect and pop open this medium, releasing an entirely new style that artists will pounce on, like kids grabbing candy from a smashed piñata.

Perhaps Indika, in time, will reveal itself to be one of these special games. The Blair Witch of video games, launching a thousand projects that build on the arthouse aesthetic. Or perhaps this abundance of creativity will — not with one bold release or one inspirational aesthetic — radically change the idea of what makes a game “cinematic” to the point that we’re less worried about how a game can look like a film, and these interactive narrative experiences that we’d previously compare to great films can have a look that’s recognizably and thrillingly their own.

I hope we get there. In the meantime, I’ll be grateful to play games that aspire to match ambitious and inventive directors, rather than playing yet another video game that could be mistaken for Free Guy.